Forests, Wildfire & Rural Communities

Improving Resilience: Forests, Wildfires and Communities

As in many countries, wildfires in the U.S. are getting worse and overly dense forests are part of the problem. A healthy demand for wood products gives landowners a financial incentive for forest thinning and other landscape restoration efforts that reduce the fire risk. In particular, mass timber creates an opportunity for large structural elements to be manufactured from relatively small-diameter trees and those affected by insects, disease, and fire. It also offers a way to strengthen rural economies. Mass timber products require sophisticated manufacturing, planning, and other plant positions—in other words, well-paying jobs in communities that often need an economic boost. So, building urban wood buildings has a very real connection to the health of our natural environment and the success of rural towns.

Overly Dense Forests

In the U.S., forests occupy about one-third of the land base. Over the past 100 years, the makeup of forested landscapes in the West has changed from patchwork patterns with natural firebreaks to forests with much greater density. Combined with a changing climate—including warmer, drier and windier weather—these overly dense forests create prime conditions for increasingly large and catastrophic wildfires.1

For more information on the impacts of forest density , watch the Ted Talk, Why wildfires have gotten worse—and what we can do about it by Paul Hessburg of the USDA Forest Service and University of Washington/Oregon State University.

Is North America running out of forests?

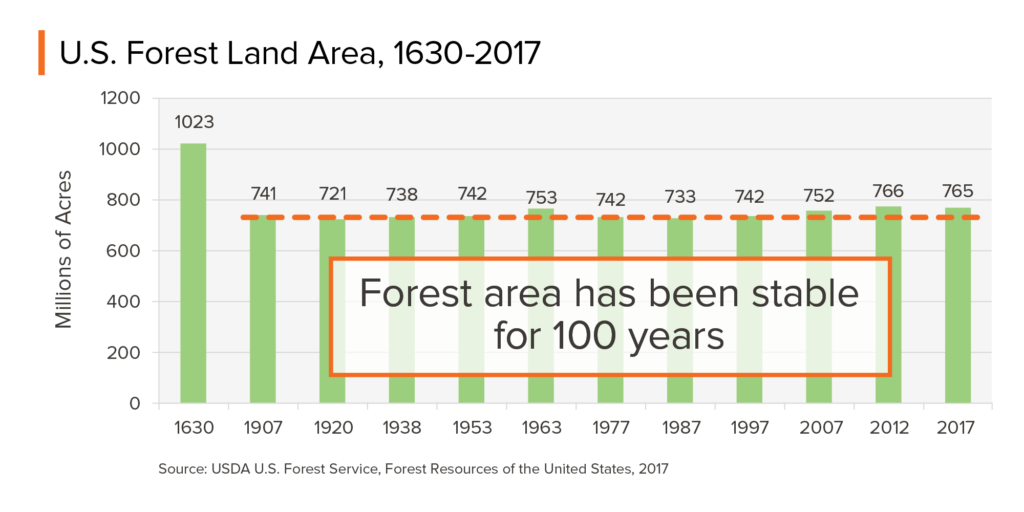

Forest area in the U.S. has been stable for more than 100 years, despite a huge increase in population. By conservative estimates, the U.S. was home to 76 million people in 1900 and there are more than 330 million people today. And yet, as shown in the graphic below, we have about the same amount of forested land as we did at the turn of the last century.

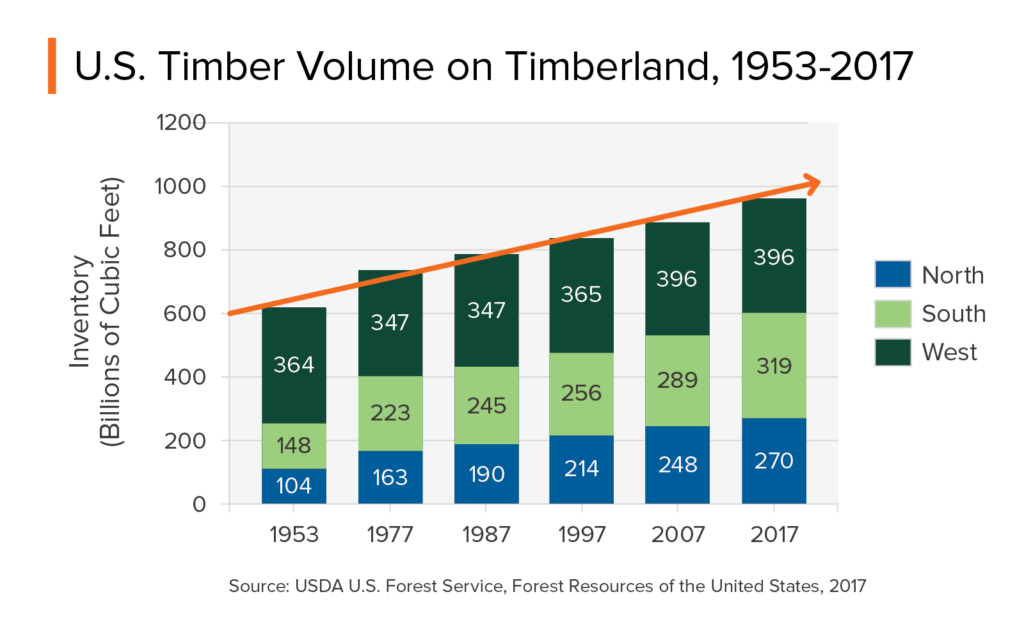

In addition to a stable amount of forested land overall, the U.S. has experienced an increase in the volume of trees on its timberlands—also known as “working forests.” These are the lands available for timber harvesting and do not include national parks or wilderness areas. An increase means net growth of tree stock, while a decrease would mean an overall loss of tree stock. The data considers all losses, including natural mortality, wildfire, and harvesting. Since 1953, the volume of timber on these lands has increased by 60%, as illustrated in the graphic below.2 Less than 2% of working forests are harvested each year.3

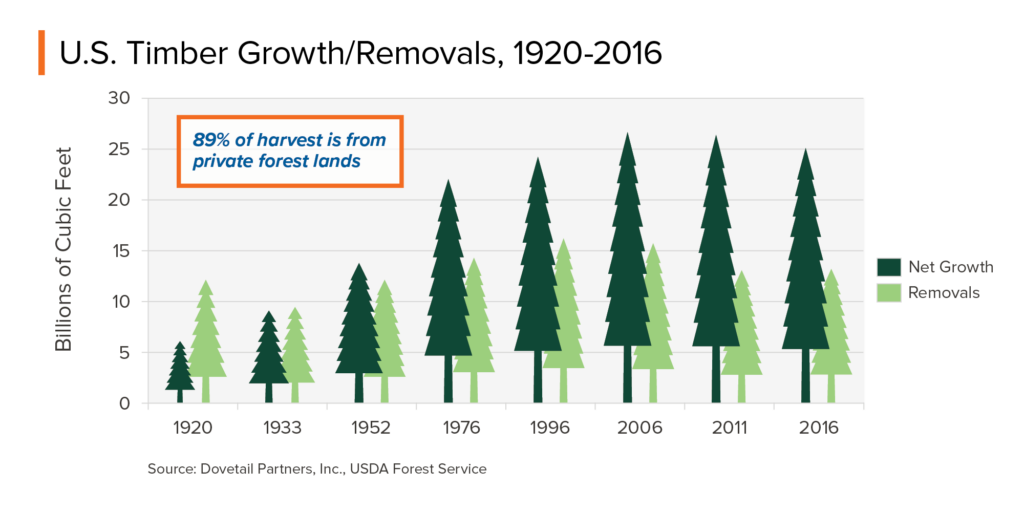

Forest growth vs. removals is another measure. The graphic below shows growth and removals on U.S. timberlands. Again, it can be seen that growth outpaces removals.

Does specifying wood contribute to deforestation?

Let’s consider the definition. Deforestation is the permanent conversion of forest land to non-forest land uses. Worldwide, agricultural expansion is the main driver of deforestation, but here in the U.S., the rate of deforestation has been virtually zero for decades.4 In the photo below, you can see an area that was clearcut and is in the early stages of regeneration. The vegetation in the foreground likely represents 10 or so years of growth following harvest.

That isn’t to say we don’t have concerns for the future. Wildfire, draught, outbreaks of insects and disease, and conversion of forested land for development, agriculture and other uses are all real issues—which strong markets for wood are helping to address.

In the U.S., 58% of the total forest land is privately owned. More than 10 million individuals, family landowners, and tribes account for 38% of this total, while corporations own the remaining 20%.3 While forest ownership in the U.S. is fairly evenly split between private and public ownership, private lands account for 89% of all timber harvested.2

What motivates these groups and individuals to keep their lands forested? Economic value is a major factor. If landowners don’t derive enough value from their forests, they’re far more likely to convert them to other uses. Likewise, the more financial incentive there is to practice sustainable forestry, the more private landowners will invest in practices aimed at long-term forest health. For example, thinning overly dense areas helps improve the health of remaining trees by reducing competition for water and nutrients. Healthier trees are able to cope better with drought conditions, have a better survival rate from insect and disease outbreaks, and recover better from small or moderately intense fires.

While focused on public forests, the USDA Forest Service is helping to build strong markets for wood products across the U.S., which will benefit both public and private lands. A priority focus of the U.S. Forest Service Wood Innovations Grant Program is mass timber, which can utilize smaller-diameter trees and trees affected by insects, disease and fire, while bringing well-paying jobs to forest communities. It is a means to support long-term sustainable forest management, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and put rural America at the forefront of an emerging industry.5

For more information on forest ownership, management, and trends across the U.S., check out these resources:

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Forest Service. (2017). Forest Resources of the United States, 2017.

Congressional Research Service. (2021). In Focus: U.S. Forest Ownership and Management.

Center for International Trade in Forest Products (CINTRAFOR), Natural Resource Spatial Informatics Group (NRSIG). (2023). Increasing Mass Timber Consumption in the U.S. and Sustainable Timber Supply.

Think Wood. (2015). The Impact of Wood Use on North American Forests.

1 Hessburg, P. USDA U.S. Forest Service, University of Washington-Oregon State University. (2020). Changing Wildfire and Climatic Regimes in the 21st Century Western U.S.

2 USDA U.S. Forest Service. (2019). Forest Resources of the United States, 2017.

4 World Wildlife Fund. Deforestation: A threat to people and nature.

5 USDA U.S. Forest Service. Wood Innovations Program.